The Life and Legacy of Rabbi Professor Yitzhak (Isadore) Twersky

Perpetuating the Masorah: Halakhic, Ethical and Experiential Dimensions

Touro Law Center and Touro Talks are pleased to present a conversation exploring the life and legacy of Rabbi Professor Yitzhak (Isadore) Twersky z"l, the Talner Rebbe and Director of the Center for Jewish Studies at Harvard University.

Speakers:

Rabbi Professor Carmi Horowitz

Rabbi Professor Carmi Horowitz is Professor Emeritus at Michlalah Jerusalem College. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University. He taught at Ben Gurion and Bar Ilan Universities, served as Dean and Rector of the Touro Graduate School of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, and was the founding Rector of Lander Institute in Jerusalem. He recently edited a volume of Professor Twersky’s collected academic writings: Kema’yan Hamitgaber: Law and Spirit in Medieval Jewish Thought.

Rabbi Dr. Michael A. Shmidman

Rabbi Dr. Michael A. Shmidman is Dean and Victor J. Selmanowitz Professor of Jewish History at Touro Graduate School of Jewish Studies. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard University, and he has published and lectured extensively in the areas of medieval Jewish history and Maimonidean studies. He co-authored, with Professsor Twersky, the course for the Open University of Israel: "Law and Philosophy: Perspectives on Maimonides’ Teaching."

Moderators:

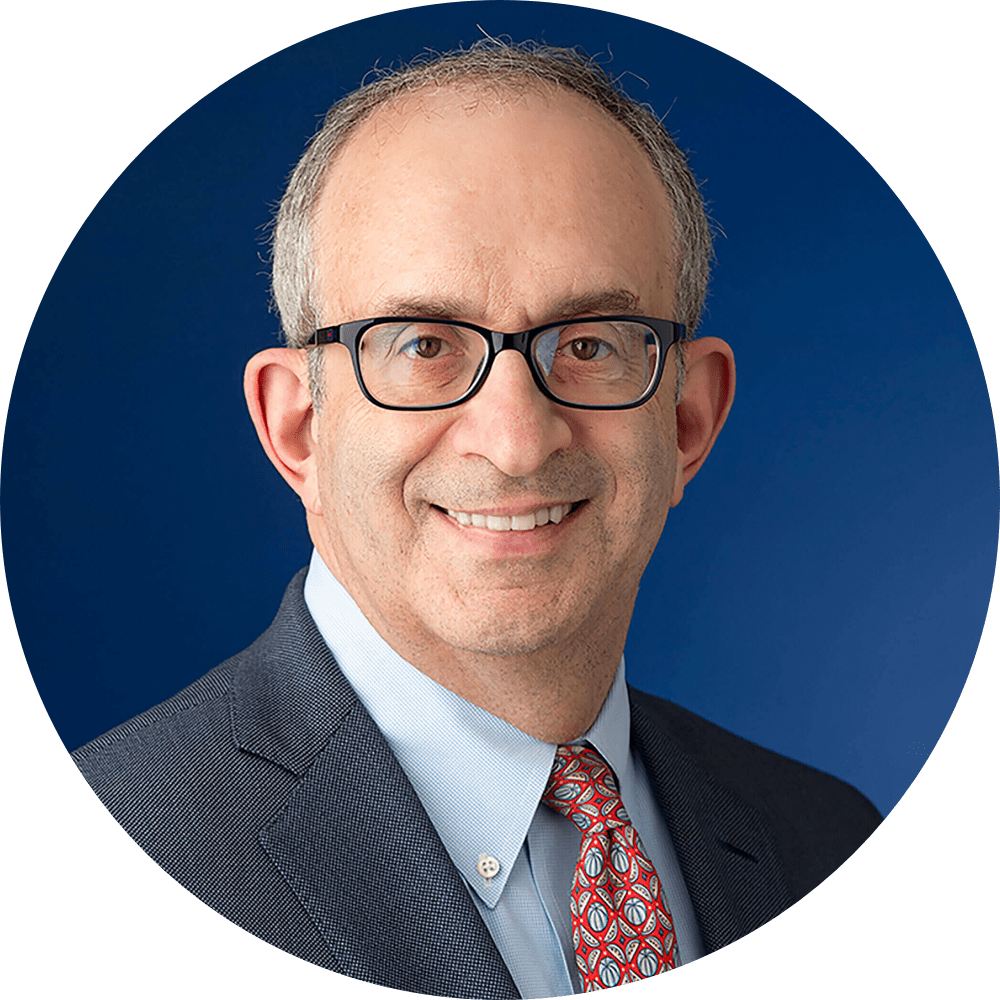

Dr. Alan Kadish

President of Touro University, noted educator, researcher and administrator, who is training the next generation of communal, business and healthcare leaders.

Professor Samuel J. Levine, Touro Law Center

Professor of Law and Director, Jewish Law Institute, Touro Law Center, prolific writer, author of Was Yosef on the Spectrum? Understanding Joseph Through Torah, Midrash and Classical Jewish Sources.

Touro Talks 2023 Distinguished Lecture Series, virtual lectures presented by Touro experts, co-sponsored by Robert and Arlene Rosenberg and the Jewish Law Institute at Touro Law Center

[DESCRIPTION] Touro Talks intro displaying photos of students and faculty across the university, fading into the Touro University logo.

[TEXT] Touro Talks, Touro University, The Life and Legacy of Rabbi Professor Yitzhak (Isadore) Twersky, September 20, 2023. Touro Talks is sponsored by Robert and Arlene Rosenberg.

[DESCRIPTION] Dr. Alan Kadish, Carmi Horowitz, Michael Shmidman, and Nahum Twersky appear in a grid-like Zoom format. The Touro University logo is at the bottom right.[ALAN KADISH]

[ALAN KADISH] I'd like to welcome everybody to Touro Talks, a conversation and presentations about an absolutely remarkable individual, whom I think we can learn a tremendous amount from. Rabbi Professor Yitzhak Twersky was a Hasidic rebbe in Boston, the Tainer Rebbe, as well as the professor-- a professor at Harvard University, where he held an endowed chair and directed the Center for Jewish Studies. The combination of these two seemingly incongruous roles led to a life of tremendous influence and tremendous productivity. And the two people we have to speak about this tonight, this wonderful, amazing individual, are probably two of the world's experts on Professor Twersky, for reasons that I'll tell you about in just a moment.

Professor Carmi Horowitz is Professor Emeritus at Michlalah Jerusalem College. He received his PhD from Harvard University. He taught at Ben-Gurion and Bar-Ilan. And we were really lucky that for several years he served as Dean and Rector of the Touro Graduate School of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem and was the founding Rector of the Lander Institute in Jerusalem. He recently edited a volume of Professor Twersky's collected academic writings, Law and Spirit in Medieval Jewish Thought, and is working apparently on another book that I assume he'll tell you about, about Professor Twersky.

The second panelist tonight is Rabbi Doctor Michael Shmidman, who is Dean and Victor Selmanowitz Professor of Jewish History at Touro University. He received his PhD from Harvard University and has published and lectured extensively in the areas of medieval Jewish history and studies about the Rambam. He co-authored, with Professor Twersky, the course for the Open University of Israel, Law and Philosophy-- Perspectives on Maimonides Teaching.

We'd like to welcome both of you. And I look forward to a fascinating discussion about a truly great scholar and man. Carmi, I believe you're going to start. Is that right? Welcome, Professor Carmi Horowitz.

I'm going to wish you both well. Look forward to hearing the discussion. And then Professor Samuel Levine, Professor of Law at Touro University and Director of the Jewish Law Institute, will handle the handle the Q&A. Thanks again. Carmi?

[CARMI HOROWITZ] Thank you. Thank you, President Alan Kadish of Touro University. Thank you Nahum Twersky, Director of Touro Talks. Thank you Professor Samuel Levine of the Touro Center for hosting the session on the Life and Legacy of Rabbi Professor Yitzhak (Isadore) Twersky as part of the program of the Touro Law School and Touro Talks. And thank you, Professor Michael Shmidman for many years of friendship, both professional and personal. It is an honor for me to be here, to be with you this evening.

The figure of Isidore Twersky exerts a very special fascination upon those who hear about the very different roles he played in his life. My goal tonight is much more modest than to provide a detailed answer to the questions you may ask. Rather, I will give you some basic facts about his life and introduce you to some of the major intellectual, spiritual issues that he dealt with. And I hope it will inspire you to learn more about and from this unusual person.

Indeed, he was a very unusual scholar, a Talmud chacham and a Hasidic rabbi. And I will share with you information about him, but mainly about his ideas, and give you just a taste of his recent book, Perpetuating the Masorah, Halakhic, Ethical, and Experiential Dimensions.

Who was Professor Isadore Twersky, also known as Rabbi Yitzchak Twersky, also known as the Talner Rebbe, who was also the son-in-law and preeminent student of The Rav, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveichik. Professor Isadore Twersky of Harvard University was a world-famous scholar of Jewish Studies. In his beit midrash in Brighton, he was the Talner Rebbe.

The book that we are discussing today is based on the lectures he gave in memory of his father, in memory of his father-in-law, in the Talner Beit Midrash. In fact, Rabbi Twersky was not only not a divided person, but there was complete harmony in his life and thinking between his academic pursuits and his commitment to Torah, mitzvot, chassidut, and emunah. Let's start with his professional position.

Professor Tversky was professor of Jewish intellectual history. That was the area that he defined at Harvard University. And you may immediately want to ask, what does intellectual history mean? Well, there's a long answer to that and a short one as well. And I will give you the short one. Intellectual history is a way of looking at a place, a span of time, and asking the following questions. What did Jews study? What did they know? What ideas were central to their lives? To what extent were Jews devoted to continuing their massorah, their tradition? And to what extent were they influenced by the culture surrounding them, both internal and external?

To what extent was the study of Gemara, for example, dominant? What was the place of biblical studies? Where did philosophy, Kabbalah, ethics, homiletics, Chassidut, Musar, biblical exegesis, poetry, where did all that fit in? And finally, what was the impact of social and political forces in the place and time being studied? Those were some of the questions that Professor Twersky asked in his research and his writing.

He was able to analyze all this by drawing on his phenomenal knowledge of the entire range of biblical, Talmudic, and post-Talmudic halakhic literature, Talmudic commentaries, codes of law, responsa literature. He was intimately familiar with the entire range of biblical commentaries to the Torah, with Jewish philosophic and kabbalistic sources, with homiletical and ethical literature. He had wide-ranging command of non-Jewish sources, those relating to areas parallel to Jewish sources, as well as social and political history.

Jews throughout the generations viewed the study and the performance of halakha and the Talmud as the source of halakhic decisions, as the linchpin, the area of prime importance in Jewish culture. In fact, they were never differences of opinion as to the centrality of halakha and to the fulfillment of halakha throughout Jewish history until modern times.

Professor Twersky dedicated a great deal of his career to the study of halakha, halakhic scholars, and to halakhic works. His first published book was an intellectual biography of the RABaD, Rabbi Abraham Ben David, the well-known halakhic critic of the Rambam.

Following that work, Professor Twersky devoted much of his career to studies of the Rambam and of maimonidean halakha and thought. His studies of the Rambam were his major scholarly accomplishments and the source of his fame. His magnum opus was a literary historical analysis of the Rambam's Mishneh Torah, the magnificent code of law that remains to this day the greatest code of halakha ever written.

His book, Professor Twersky's book, Introduction to the Code of Maimonides Mishneh Torah is a brilliant, innovative, profound study of Maimonides code of law, teeming with insights and new understandings of the Rambam. Let me briefly share with you one important insight of Professor Twersky, which resulted in a paradigm shift of how to understand the Rambam's intellectual universe.

A close reading of Rambam's laws of the Mitzvah of Talmud Torah, the study of Torah, is the centerpiece of the proof of his theory. In the history of scholarship on the Rambam, there were many who claimed that there was an inherent tension, even a dichotomy, between the Rambam who wrote the Mishneh Torah, and Maimonides, the author of The Guide of the Perplexed, or Moreh HaNevukhim.

The reigning view was that Mishneh Torah represents a strict, comprehensive, halachic regimen, and The Guide reflects a sophisticated philosophical approach to Judaism. There were those who even saw The Guide, in the guide, ideas that perhaps undermined the authority of halakhah. And in his writings, Professor Twersky demolished that approach by demonstrating the harmonious relationship between the two works, and that, in fact, there is extensive of integration of philosophy and philosophical positions in the Mishneh Torah.

One of the important proofs of this theory emerges from the way the Rambam defined the scope of the mitzvah to study Torah. When discussing in the Mishneh Torah the various categories of the mitzvah of the study of Torah, the Rambam writes, and these are his words, "The topics termed 'pardes' are included in the study of the Talmud. The word 'pardes' literally means an orchard, but it is a metaphor that chazal use as a symbol for esoteric studies, topics that are not accessible to the wider public.

In the Talmud, there is no explicit definition of what those exoteric studies contain. However, the Rambam in the Mishneh Torah explicitly identifies pardes as embodying philosophic knowledge. By including pardes as part of the Talmud, part of the study of Talmud, an integral part of the oral law, Rambam gave it halakhic legitimacy by assigning to it the status of an important goal for every Torah scholar to teach.

This philosophical approach provided the underlying and overriding moral, ethical, and spiritual messages of the halakhah, and the Rambam saw in them the pinnacle of human, religious, and spiritual perfection. Thus, Professor Twersky showed that, according to the Rambam, philosophical metaphysics are not only important, and not only are they integrally related to halakhah, but he assigns to them the status of the ultimate goal of Torah study. The Rambam did not see a conflict between philosophic rationalism and Halakhah. Philosophic rationalism strengthened the halakha, and he saw them dwelling together in mutual reinforcement relationship.

Let me take this one step further. Central to Professor Tversky's scholarship was that, not only did we witness this harmony in the Rambam's works, but also, all through the generations, halakhah did not stand by itself. Scholars saw the need to supplement the study of halakhah with additional areas that would provide the spiritual foundations of the halakhah. Professor Twersky formulated an important principle in one of his articles, which I present to you now in my paraphrase.

"Halacha has meaning and significance beyond the simple physical action of the mitzvah. There are halakot, whose purpose is to inculcate ethical and moral principles. There are mitzvot, whose goal is to trigger the memory of historical experiences. Others embody religious beliefs and convictions. Only study and reflection will sensitize a person and stimulate him to an awareness of these goals." Those are his paraphrased words.

The body of knowledge that one should study to accomplish these goals to reveal the ethical and moral principles inherent in the halakha to sustain the memory of historical experiences, Professor Tversky called meta halakha, that which is beyond halakha, or better, that which raises a person to the heights to which halakha intended.

What is the discipline? Or more precisely, what are the disciplines that can supply meaning to the halakha? The answer to that question has a long history, and one of Professor Tversky's goals was to describe and chart those disciplines and their relationship to Halakhah throughout the generations. Prominent among them are philosophy and Kabbalah, each in its own way, despite the difference in their content-- and philosophy and Kabbalah differ considerably, of course-- but they had similar goals.

Professor Twersky traced the ways that both philosophy and Kabbalah provided systems of values and interpretations that complemented the halakhah, and provided the observers of Halakhah to find spirituality, morality, and ethics that turned the Halakhah into a dynamic spiritual experience.

This is a very rich history. There is a very rich history of this approach, and Professor Twersky documented and described this history in his writings. He planned much more, but we were [SPEAKING HEBREW]. He unfortunately passed away at the young age of 67.

Rabbi Professor Twersky's academic writings was as profound as it was all encompassing. Many of his articles deal with Jewish religiosity and spirituality. Although writing in a scholarly mode, the discerning reader can sense an undercurrent of identification, of passion, of an almost experiential fusion with such topics as halakhah and spirituality, and of concepts of kedushah and of kavanah, that is, focused intention and prayer, which he saw in the writings of the Rambam. Professor Twersky's writings about great rabbinic scholars, such as the Rambam, the Rabad, Ramban, Rabbi Joseph Karo, the author of the Shulchan Aruch and many, many others also revealed his admiration for these important scholars.

The Talner Rabbi, beyond Rabbi Twersky's achievements in the world of academia, he served as the Talner Rabbi in his beit midrash Beit Hamidrash Beit David in Boston. Rabbi Twersky succeeded his father, Rabbi Meshullam Zusha Twersky, who came from Europe to Boston about 100 years ago and passed away in 1972. Rabbi Twersky prayed, taught Torah, and guided his congregants in that beit midrash.

He was deeply committed to his role as a Hasidic rabbi. And while he dispensed with some of the externalities of Hasidic garb, he saw himself as a link in the chain of Hasidic tradition, going back to the Me'or Einayim, Rabbi Menachem Nochum of Chernobyl. The latter was a student of the Baal Shem Tov and the Maggid of Mezritch and founder of the Chernobyl dynasty.

His grandson and founder of the hesed, his acts of loving-kindness, which characterizes the Hasidic personality and certainly the Hasidic rabbi, was extensive and sensitive, yet covert and concealed. He dedicated time to listen sympathetically to those who needed his advice. He taught a Torah of hesed, loving-kindness, and his simchah. His joy on Simchat Torah and other occasions was intense and visible.

The essays in perpetuating The Masorah, the latest book of his that appeared, provide us with a glimpse of his passionate commitment to Torah, to Jewish tradition, and to its survival. The essays were oral shiurim, oral lectures that Rabbi twersky delivered in memory of his father-in-law, the Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveichik, and were edited from recordings by Rabbi Dovid Shapiro and myself.

The four topical essays of the book, the first four chapters, are not hespedim, in his memory, but independent Torah reflections. Whereas, the last chapter of the book originally appeared as a hesped for The Rav in the journal tradition. And Rabbi Dovid Shapiro and I lightly edited it for this volume. The hesped is a soaring, inspiring tribute to The Rav.

The book thus reveals one more facet of Rabbi Twersky's legacy. And that is the profound impact that The Rav had upon him and his thinking. That impact is obvious, not only in this volume, but also in many of his scholarly articles as well. Rabbi Twersky writes in his introduction to his book, Introduction to Mishneh Torah, how he-- and I quote him-- "repeatedly benefited from his father in law's immense and genuinely effervescent learning. He has given me so much over the years that it would be folly to assume that formal acknowledgment would be fully expressive." Close quote. The two of them studied together every Friday morning for many years, and after Rebbetzin Soloveichik passed away, The Rebb lived with the Twersky family.

On a personal level, Rabbi Twersky was a man of genuine modesty, who had a strong distaste for any kind of artificial publicity or fame. This modesty expressed itself in an understated ardor and passion in his actions as well as in his writing.

Yet, his deep ahavat Hashem, love of God, and yirat shamayim, his intense kavanah could be attested to by the personal experience of davening in the Talner beit midrash, by meeting the Talner Rebbe, hearing him deliver a classic shiur in Talmud, short and incisive divrei Torah at a [SPEAKING HEBREW] at the Talner beit midrash.

At times he delivered longer, fully-developed shiurim, all of which were blended with original creative understanding of Torah verses, of Talmudic discussions, and of aggadic homilies and narratives. And most important, significant ethical and moral guidance, sometimes explicit and often by clear implication. The readers of the essays in this volume will get a glimpse of all of the above.

They are not intellectually detached academic essays, but rather edited transcriptions of his carefully crafted oral shiurim, some of which were partially written out in longhand. Commitment to the masorah, the passion and love of Torah, the excitement of understanding [SPEAKING HEBREW] Torah, the inner spirituality of Torah, all flow from the words and between the words of these essays.

What are the themes of perpetuating the masorah? The essays in this volume all relate to the content of the masorah, the tradition of the written and oral law revealed at Mount Sinai, its preservation and transmission throughout the generations. And some of the topics that appear in the book are the teaching of Torah to whom? To everyone? Only to scholars? What are the ways of teaching Torah? How does one become a Torah scholar? What are the prerogatives of Torah scholars? And what are their responsibilities and obligations? What are the qualities of teachers of Torah as well as students of Torah? What are the unique aspects of the masorah of Jewish tradition emphasized in this book?

The masorah emphasized the centrality of law, which included its observance, as well as the heavy intellectual demands of its study, while simultaneously giving a place of preeminence to religious spirituality, and to moral and ethical living. This fusion of law and spirituality, as we have already seen, was a central focus in Professor Twersky's academic writings. But for him, the topic was existential as well. It lay at the very heart of his own religious consciousness, his own spiritual commitment to a life of kedusha, of holiness.

It was a cherished and honored feature of the spiritual legacies he had inherited, the Hasidic tradition he received from his father, and the intellectual, spiritual heritage that he received from his father-in-law. The cluster of concepts, spirituality, intellectual-spiritual, religious, moral, ethical, are in fact a leitmotif in the chapters of this book, evoking fundamental ideas and ideals of his thought.

And I repeat once more, in his view, not only as a historian but as a Hasidic rabbi, one cannot separate the legal halachic norms, which are the external manifestation of Judaism from, as in his words, the internal sensibility and spirituality that is [INAUDIBLE]. The theme of halakhah and spirituality reverberates throughout the generations. And Professor Twersky pays close attention to its dynamics in the chapters of this book.

To concretize the book's message, I will share with you some short insights from the first chapter of the book, which is called "Raise Up Many Disciples." The first chapter of Pirkei Avot opens with a well-known triple saying of the Anshei Knesset Hagdola, The Men of the Great Assembly. And the Mishnah states, [SPEAKING HEBREW]

They said three things. Be patient in the administration of justice. Raise up many disciples, and make a fence around the Torah.

What are the implications of this middle phrase, raise up many disciples? If Chazal speak of raising up many disciples, one question that needs to be addressed, what are the qualities of the ideal teacher of Torah? And Rabbi Twersky says one of them is, hesed, compassion. And in his words, hesed is compassion, kindness, benign involvement in the development of others.

And he continues, in order to fulfill ha'amidu talmidim harbeh, one must believe in the people who are listening, in the people who are studying, in the people who are eager to learn. One must feel that they are worthy, that they are receptive, and that it is a proper investment of time and energy to share Torah with them and to expose them to Torah.

The second prerequisite for raising up any disciples is [SPEAKING HEBREW], humility. Rabbi Twersky defines it as an inner directed quality that frees one from all pompousness and officiousness, that helps rid one of artificiality and pretense. And he continues in the following words, "A proud, condescending, self-centered person, who ponders every step and every gesture, no matter how learned, will not be influential and successful as a transmitter of the Masorah as a master of Torah. You must bring yourself to the level of intelligent, inspiring communication with everyone who is eager to advance and to acquire learning."

The third prerequisite for raising up many disciples is that there must be an effort to instill self-confidence in the students of Torah. Colloquially, this idea is expressed as ha'amidu talmidim, literally ha'amudi, raise up, let them stand on their own two feet. The teacher should help the talmidim achieve independence by elevating them and encouraging them to develop, not to remain dependent both intellectually and spiritually.

In his analysis of ha'amidu talmidim harbeh, raise up many disciples, he points to three additional aspects of fulfilling the instructions [SPEAKING HEBREW]. The first is, to whom do we teach Torah? Based on analysis of Hazal's comments on the verse of Veshinantum Levanecha, you shall teach your sons diligently, Hazal draws the following conclusions. The first is that the obligation to teach Torah is not only to your children but to everyone. A talmid chacham, a scholar, has an obligation to perpetuate the masorah by teaching Torah to all that desire the knowledge.

Secondly, they derive from this verse that Torah must be taught in a comprehensive manner, that is, all parts, the written Torah, the oral Torah, the methodology of halakhic thinking, as well as what he called the meta halakha. And the third implication, and these are all spelled out in detail in the book, is that the Shinantum implies that your grasp of Torah should be precise and sharp so that you can expound Torah with maximum clarity.

Rabbi Twersky goes on to explain that there is one more crucial component to the teaching of Torah to ensure that the masorah will be perpetuated. That is the personal dimension of Talmud Torah. The study of Torah is not only an intellectual exercise. Our connection with Torah involves the qualities of love, the [SPEAKING HEBREW], the feeling of fear and awe, the sense that when studying Torah, the Shekhinah, God's presence can be felt. And if that is so, then a teacher of Torah must share his own emotional, experiential connection to Torah with his students.

Rabbi Twersky tells us that this is what is meant by Nishmat Hatorah, the soul of the Torah. The Ramban, Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman, is of the opinion that there is a mitzvah never to forget what we saw at the time of the giving of the Torah. And Rabbi Twersky says, and these are his words, "The Ramban is of the opinion that the mitzvah is not referring to a prohibition of forgetting the content of the mitzvah, of the mitzvot, but rather, not to forget the circumstances, the experience of receiving the Torah. It refers to the excitement, the exhilaration, the encounter with God that accompanied and continues to accompany the study of Torah and the performance of mitzvot. All this can be summarized in the words Ma'amad Har Sinai, the very experience of being present at Mount Sinai when the Torah was given."

It is for this reason that Ramban states, studying about the belief in Torah is itself the study of Torah. Not only does one need to study the halakha that spell out the details of the practical mitzvot, we need to study the basis of our belief in Torah, which sustains our understanding of and attachment to Torah.

Thus, raising up many disciples must include the effort of the teacher to understand Nishmat Hatorah and transmit the inner experience of Torah. Learning means not only from books. It also means learning from the living representatives of the masorah. And Rabbi Twersky goes on in detail, explaining this crucial aspect of raise up many disciples. But that will have to be left to your reading of this description in summary.

I introduced you to Rabbi Yitzhak Isadore Twersky at Harvard University and the Talner Rebbe in Boston. We made a brief acquaintance with his academic work, with particular emphasis on his study of the Rambam and on the theme of religion and law, or halakha and spirituality. We then met the Talner Rebbe and discovered that many of the same themes that Professor Twersky dealt with in his scholarly work were the themes that he taught in his beit midrash as well.

This very brief account of his work and his life gives you a mere glimpse of a giant Torah scholar and one of the greatest Jewish historians of the previous century. I recommend to you, reading his book, Perpetuating the Masorah, Halakhic, Ethical, and Experiential Dimensions so that you can directly absorb his penetrating Torah insights on your own. Thank you.

[CARMI HOROWITZ] It is an honor to follow my esteemed colleague and very dear friend of many years, Professor Horowitz and to try to compliment his highly insightful words with a portrait of harav Professor Twersky drawn through the eyes of a student. And I have entitled these remarks [SPEAKING HEBREW], "A Student's Personal Reminiscences."

In the summer of 1974, just prior to my first semester of doctoral studies at Harvard, I met with Professor Twersky [SPEAKING HEBREW] to plan my fall semester schedule. Professor Twersky inquired about my activities since my interview with him the previous November at his home, and I replied that I had just completed Yoreh Deah examinations for Smicha for rabbinical ordination.

"In that case," countered Professor Twersky with a hint of a smile, "you must be familiar with Ibn Kaspi's response to an inquirer concerning a milchig spoon accidentally inserted into a fleishig pot." Embarrassed to admit outright that I had never heard of Ibn Kaspi, I hesitated before finally acknowledging that I did not quite recall Ibn Kaspi's statement. Professor Twersky then returned to the logistics of the fall semester schedule, without revealing to me anything more about Ibn Kaspi or the offending spoon.

Upon returning to Widener Library, I researched the 14th century exegete and philosophic writer Joseph Ibn Kaspi, his ethical will and anything else I could uncover about him. In subsequent semesters, I was to become quite familiar with Ibn Kaspi, until one day in 1977 or early 1978, when Professor Twersky handed me a draft of his classic essay "Joseph Ibn Kaspi, Portrait of a Medieval Jewish Intellectual, later to appear in volume one of Harvard Studies in Medieval Jewish History and Literature. And he requested that I read and comment on the draft prior to publication. At that moment, I felt a true personal sense of vindication in the matter of Ibn Kaspi and the misplaced spoon.

In retrospect, this early experience was paradigmatic of the nature of my student-teacher relationship with Professor Twersky. Three of my first four courses at Harvard were seminars with him, mostly focusing on maimonidean-related issues and texts. I was one of two entering doctoral students that year, with some more veteran students attending the seminars as well.

For the first month or so, these seminars usually commenced with one of us, the new students, reading a text and then being asked a series of questions that, for the most part, we simply could not answer. With my ego deflated, I spent the Sukkot break from classes meticulously examining articles by Professor Twersky on the Rambam, wherever possible tracing footnotes back to their sources and endeavoring, in the words of the subtitle of Professor Harry Wolfson's book on Spinoza, quote, "to unfold the latent processes of his reasoning," unquote.

The day classes resumed. I met Professor Twersky while coming up the elevator to class, and he inquired whether I was now prepared. I was in fact, very well prepared that day. And soon after, as I continued to better understand and anticipate the methodology of his questions and the nuances of his textual observations, I hoped that I might even merit to be called by my given name, like the other veteran students, instead of just Shmidman.

That sense of vindication was to wait, however, until later in the spring semester, when one last trial had been successfully withstood. I referred to the trial by fire, officially known as the Hebrew 224 Seminar. At that time, we would sit around the table in Room G on the third floor of Widener Library. I guess today we would call it the room where it happened. And a student would present a paper for critique by fellow students, and especially by Professor Twersky and Professor Yosef Yerushalmi, who sat respectively at the two ends of the long table.

My fall semester presentation on Ramban Nachmanides actually was very well received in its final written form and presented later at various forums. But my oral presentation of essentially the same paper was flawed by some imprecise formulations, with predictably disastrous results.

Feeling crushed by the experience, I tried to react as in the other previous instances. So for the spring semester 224 seminar on Rashba, I chose the subject of Rashba as halakhic critique of Maimonides and threw myself into a thorough investigation of how Professor Twersky presented the Ra'avad, the Ra'avad, as critic of the Rambam. What questions did he ask? What literary categories and historical context were useful? The resulting presentation, later published, went without a hitch. Most important, from that time on, I was always called Michael. That appellation provided once again a sense of vindication, along with a profound feeling of elevation.

I recall these personal experiences in order to illustrate what I believe to be an outstanding trait of my mentor, a trait that sometimes is overlooked in the discussions of his illustrious legacy. And that trait was his gift for skillful and effective pedagogy. And here I believe I am complimenting what Dr. Horowitz, what Professor Horowitz spoke about just a few minutes ago concerning the ideals of teaching and pedagogy as presented by Professor Twersky himself.

My experience, still so vivid, was that of sitting at the feet of a master pedagogue, an awe-inspiring scholar, who continually and insistently challenged and stimulated us, his students, to raise ourselves to his rigorous standards of scholarship, who taught us to appreciate how much we did not know, while providing us with the methodological tools to acquire some of that knowledge.

Professor Twersky once told me that in any discipline of study, whether Talmud or history, one requires a derech, a method of studying texts that involves asking the right questions of the text. And it was precisely that, a derech ha-limmud that we gained from our mentor.

Permit me to reminisce about one more of Professor Twersky's characteristic traits, one that I think has sometimes been both overlooked and mischaracterized. I refer to his personal warmth, and here I am reminded of the Genizah Fragment published by Paul Fenton in 1982, which tells the story of an individual who is on his way to visit the Great Sage of Fustat, presumably Maimonides, and who is apprehensive about the meeting, especially since his young son is accompanying him.

To the visitor's surprise and relief, the great rabbi, in the company of his own young son, is warm and hospitable, serving lemon cakes and playing with the visitor's child. The story suggests that the image some might have of an austere, intimidating, coldly-rationalist Maimonides is in need of revision.

I think that to some observers, Professor Twersky's careful and precise weighing and measuring of seemingly every word he spoke and wrote, his aversion to small talk, his commanding brilliance, his complete control over his outward emotions, and his acceptance of no less than first-rate performance from his students and colleagues, might have created an image of an austere academician lacking in personal warmth.

If, however, warmth is to be measured not by the number of slaps on the back and smiles per minute but rather by a deep and abiding concern and caring for others, in this case one's students, then I submit to you that Professor Twersky was one of the warmest people I have ever met. I could catalog expressions and manifestations of that caring and that concern at some length. A few personal examples, however, must suffice at this time.

In 1977, I was making headway in my dissertation research, and Professor Twersky inquired about my career plans, asking me if I desire to pursue an academic career, while warning me, quite accurately, to expect [SPEAKING HEBREW], in other words, meager financial reward as a condition of academic employment. When I responded by expressing my desire to apply for a full-time academic position, he immediately supported my decision. And I soon found myself, with his help and recommendations, very much in demand.

Subsequently, whenever I was confronted with an offer of a new position or sought a change, I discussed each offer with Professor Twersky, who agonized over the decisions, along with me and my wife, and never failed to offer practical advice, wise counsel, and invaluable assistance in opening the right doors.

Wise counsel was not limited to decisions concerning job opportunities. As dean of a graduate school for four decades now, I have often faced difficult administrative decisions. And my mentor was always there for me. Whether I required his help in creating a new curriculum, evaluating candidates for faculty positions, reviewing sensitive proposals to be sent to New York State Ed or accrediting agencies, or even personally intervening to save one of our programs from being unfairly derailed, he was immediately available, and his assistance was indispensable. In this, and so many other capacities, his presence has been sorely missed.

Professor Twersky also attempted to advance my academic standing in every way he could. As just one example, he called me in 1982, prior to the three-day international conference that he had organized at Harvard on Jewish thought in the 17th century and invited and invited me, just a recent graduate, to chair the opening session and present a review of the already distributed papers to be discussed at the three-hour session. All this in order to provide me with both experience and exposure in the presence of most of the major senior scholars in the field.

I might add at this point that, as founding director of Harvard's Center for Jewish Studies, which he headed for 16 years, he organized numerous major one or multiple-day international academic conferences on subjects ranging, for example, from the Rambam, the Rashba, and Ibn Ezra, to Jewish thought in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, respectively. Many of the proceedings were subsequently published. Dozens of Israeli scholars were invited to the conferences and/or invited to the Center as visiting scholars.

In this way, Professor Twersky may well have accomplished more than any one scholar in those decades in forging close bonds between American and Israeli scholars and departments of Jewish Studies. Professor Twersky also afforded me an unusual scholarly opportunity early in my career. He asked me to assist him in writing a textbook in Hebrew for the Open University of Israel, [SPEAKING HEBREW], a two-volume work entitled [SPEAKING HEBREW], English title, Law and Philosophy, Perspectives on Maimonides Teaching.

For someone like myself, who so admired my mentor and so enjoyed studying Rambam, the project was the academic equivalent of baseball fantasy camp. We worked on the book in spurts from the early 1980s, sometimes intensively, for a month or two in the summer, sometimes not touching it for an extended period due to our respective schedules, but always returning to it for further periods of collaboration until the second and final volume was published finally in 1995. It was an extraordinary privilege to serve as co-author of volumes presenting the teachings of my teacher concerning the teachings of the teacher of Klal Yisrael, the [SPEAKING HEBREW], the Rambam.

There is much to recount concerning that project, much that I learned from and about Professor Twersky in our work together. For one thing, I learned to fully appreciate that the comments cited by Chaim Heller in his introduction to his edition of the Rambam Sefer HaMitzvot in the name of the 16th-century [SPEAKING HEBREW]

--that one should examine the words of the Rambam as meticulously as one examines the words of the Talmud itself can be applied to the exceedingly precise words and writings of Professor Twersky as well.

But my focus now is simply the trait of personal warmth, and so I emphasize only that throughout this entire period of our literary collaboration, Professor Twersky treated me, not only as a respected colleague, but also as a beloved son. He and his wife, Rebbetzin Twersky [SPEAKING HEBREW], opened their home to me and made it clear that I was to consider myself a member of the family, with an open invitation to stay and eat at the Twersky home on my trips into Boston to work on the project.

Professor Mrs. Twersky regularly inquired about my wife and children and their progress, as they had done when we lived in Cambridge. Indeed, Professor Twersky served as sandek at the birth of one of our children who was born in Cambridge. Even in my last visit to his home in 1997, when he was recuperating from the effects of medical treatments, he refused to speak about himself, focusing only on my plans and the welfare of my family. His eyes, sometimes so piercing and intimidating in a classroom setting, radiated only happiness despite his condition as he heard news of the imminent births of our first grandchildren, the same happiness and joy that radiated whenever he discussed or was in the company of his own grandchildren.

And of course, at that meeting he talked Rambam, discussing a difficult formulation in [SPEAKING HEBREW] malachim, observing that every time he carefully learns Rambam, he finds something new, and reiterating that the issue in the study of Rambam is not so much the uncovering of further new sources of the Rambam's words, but rather the exploration and comprehension of the Rambam's creative minds at work in his interpretations of rabbinic sources.

In 1995, our daughter was married and soon after our eldest son as well. Despite the pressures of a busy schedule on those dates, he flew into New York for both weddings, flying right back to Boston immediately after his presence and participation under the chuppah. [SPEAKING HEBREW]-- write them on the tablet of your heart, exhorts the verse in Mishlei.

There are many images retained in my mind's eye that involve harav Professor Twersky, but two images in particular stand out in sharp relief, and they concretize the two traits that I have chosen to highlight. The first image is that of Professor Twersky sitting in the Harvard captain's chair at the head of the table in Room G, conducting a seminar and suddenly focusing his intense gaze upon me, challenging and motivating me and the other students to meet his standard of scholarship.

The second image is that of a warm and joyous embrace, the memory of the way he embraced me under the chuppot of my children. Those images, those teachings, and that warmth remain embedded within me, [SPEAKING HEBREW], inscribed upon the tablets of my heart. Thank you.

[NAHUM TWERSKY] Thank you, Professor Shmidman. Thank you, Professor Horowitz. I believe we have some time for some questions and answers. I'd like to turn the floor over to Dr. Sam Levine.

[DESCRIPTION] Samuel Levine joins.

[SAMUEL LEVINE] Thank you so much, Nahum. And on behalf of Touro Law School and the Jewish Law Institute, I want to express my appreciation to Professor Horowitz and Professor Shmidman for such a thoughtful and thorough presentation that gave us a sense of Professor Twersky for those of us, many of us, who never had the opportunity to know Professor Twersky, of both the person, the academic, the scholar, the town Rebbe, the Harvard professor.

On that note, many of us are taken by the emphasis on the Rambam, om Maimonides. And Professor Horowitz I think implicitly, and Professor Shmidman more expressly, drew comparisons between Professor Twersky and the Rambam in this ability to bridge these different worlds. And the Rambam likewise, of course, bridged many, many worlds, many, many cultures, and many, many disciplines. And we're wondering if it was not a coincidence that Professor Twersky focused so much on the Rambam. Any scholar of Jewish law, of course, would be taken with the Rambam, but I think it's fair to say his magnum opus and so much of his work was dedicated to exploring the Rambam in such a sophisticated manner.

[MICHAEL SHMIDMAN] So to Professor Levine, very insightful point, I think. Yes, this is a fascinating and remarkable affinity between the scholar and the dominant subject of his research. And I think that Professor Twersky, despite the fact that he never, to my knowledge, consciously expressed this link, I believe he was drawn to the Rambam for various-- because of various affinities, striking affinities between the two in their life and their work.

In terms of their life, as Doctor Horowitz pointed out earlier, the Rambam was, of course, the rabbinic scholar and communal leader on the one hand and the contemplative philosopher on the other hand. And it was Professor Twersky who insisted that, as professors mentioned, that you should not bifurcate the Rambam into those two separate individual. He was, after all, one individual. And you try to find the way in which the Rambam unified both dimensions of his character and interest in his writings.

And Professor Twersky himself was on the one hand the Talner Rebbe and a leader of his kehillah, on the other hand, the Harvard professor. And as was stated earlier, and also, if you look at the book edited by Professor Horowitz, in the introduction, you'll find the paragraph from Professor Ezra Fleischer in which he talks about the overall-- the overriding harmony and unity in Professor Twersky's own life, this inner harmony that he felt. Even if some onlookers might see some kind of a tension or some kind of incongruous relationship between the different dimensions of his personality, he himself experienced an inner harmony.

And part of that has to do with another affinity between him and the Rambam that probably drew him to that study. And that is the emphasis on the issue, again, as Professor Horowitz underscored, of law and spirituality. To Professor Twersky, this was key. How does halakhah, the normative system, concretize religious experience, theological postulates, et cetera, from the time you wake up to the time you go to sleep in the concrete actions of halakha? What happens when there seems to be a disconnect between your normative actions and what they're supposed to concretize? And it becomes like Yeshayahu, Isaiah, said, mitzvot [SPEAKING HEBREW], like a rote artificial type of action, mechanical action.

These matters were key to the Rambam's thinking. And Professor Twersky in his own writing, which you can see in this latest volume of essays, and also in the volume of divrei Torah that he transmitted at [SPEAKING HEBREW], at the Talna. You can see the blend, the merger, between the fusion, between law and spirituality in Professor Twersky's own thinking, the focus on that theme. So again, there was this affinity. And finally, I think there are other affinities. But I would mention that, like the Rambam, Professor Twersky refused to take any remuneration for his role in leading his community in Boston. That's correct, right, Carmi?

And in this one case, whereas, I never otherwise heard him talk about this conscious link between him and the Rambam, I recall hearing from our colleague, Professor Bernard Septimus once that here Professor Twersky did state that he was trying consciously to emulate the Rambam's ideal of leading-- being a rabbi or a dayan, or a teacher of Torah, without taking communal funds, [SPEAKING HEBREW]. And these are just some of the numerous affinities that are so striking between Professor Twersky and the Rambam. And it's no surprise to me that he was drawn to that study and was able to extract those same features. I'll give it over to--

[CARMI HOROWITZ] I agree with everything that you said, and let me just add two things. I once heard him say-- or was it quoted by his son, I think. Maybe it's quoted from his son-- that he would have liked to have been born in one of two periods, in the time of the Rambam or in the time of the Baal Shem Tov. And those were two foci.

But I would like to quote two or three lines from a footnote in one of his articles, where he says that "it should be stated unequivocally that there is no natural alliance between spirituality and anti-intellectualism, as it is often the case in the history of religion." I skip a little. "One way to achieve spirituality is by study, understanding, rationalization, emotionalism, or sensuousness are not the exclusive, not even the preferred means toward heightened sensitivity and spirituality. Rationalism and spirituality are congenial."

And I believe that his Hasidic persona sustained his intellectual, academic persona, and they melded that way. And they fit together because-- and he brings many proofs here that spirituality can be achieved through rationalism and not necessarily from reading pirkei tehilim in an exuberant way. So I think that that characterizes him, and that I think we get a picture of why he was so drawn to the Rambam.

[MICHAEL SHMIDMAN] Yeah, I agree, also, wholeheartedly with what Professor Horowitz said. And I highly recommend the article that was just cited. The footnote was from Religion and Law, I believe, which is a classic piece by Professor Twersky on the ideal balance between law and spirituality that the halakhah seeks.

[SAMUEL LEVINE] So we have a question from the audience in particular as to whether you happen to know of any plans to reprint some of Professor Twersky's books that have been out of print.

[CARMI HOROWITZ] Well, we issued a collection of 31 of his articles. But living in Israel, I made sure that they were all translated into Hebrew. That appeared a number of years ago, and a major collection of all his articles. I am right now seeking a way of having them all appear in English, and I'm in touch with a number of publishers in that direction. And we very much hope to be able to do that and to make them accessible in English as well.

And as well as president alluded to the fact that maybe I shouldn't jump the gun, but I'm working right now on an intellectual biography of Professor Twersky, which will be-- one of its goals is to present his major ideas in an accessible way.

And his own writings were very, very, I would say, written in a very tight, formal way with high-level language, and they're not easily read. And one of my goals in the book that I am writing now is to bring it out and to be able to make these ideas accessible and [SPEAKING HEBREW] that the book will come out.

[NAHUM TWERSKY] I think in that spirit, we will wrap up this wonderful, brilliant discussion, presentation. I am really enamored with your presentations. And from the bottom of my heart, I just want to thank the two of you. Thank Dr. Levine as well, and Dr. Kadish. The video of this presentation will be available shortly and hope to make it available for all those who want to see it.

In the spirit of these days, again, before Yom Kippur, I pray that everyone have a healthy year, a spiritually fulfilling year. I used to daven at my cousin's at 64 Quarry Road. And perhaps, it relates to some of the most meaningful [SPEAKING HEBREW] that I enjoyed over time.

So all my best to you. I want to thank you again and wish everyone a [SPEAKING HEBREW], one that is filled with joy, happiness, and good health. Thank you all for joining.

[CARMI HOROWITZ] And thank you, Nahum. Thank you, Nahum, for your initiative and bringing your cousin and our Rebbe's Torah to a wider audience.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

[NAHUM TWERSKY] Thank you.

[MICHAEL SHMIDMAN] Thank you, Nahum. May we live up to his legacy indeed.

[NAHUM TWERSKY] Amen.

[TEXT] Touro Talks, Touro University, touro.edu/tourotalks

[MUSIC FADES]

/prod01/channel_38/media/redesign/assets/images/background-images/locations-background.jpg)