What His Students Say

Dr. Domingo was my dissertation chair. His mentorship, professionalism and extraordinary patience was undeniably part of my success. I don't think I could have done it without him. I will always be grateful.

—Dr. Craig Gold

Dr. Aldwin Domingo’s success story is the classic American immigrant story.

Domingo was born in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines. When Domingo was a child, his father emigrated to the United States to help pave the way for the rest of the family. During the nine years before the family was reunited, Domingo’s father only returned home twice. Domingo recalls hearing messages from his father on many double-sided cassettes that his mother received from the United States over the nine years.

“My father saw the writing on the wall,” recalled Domingo. “The Philippines was going through a lot of political and economic turmoil and my parents realized that coming to another country was the best way to improve our standing in life.”

When the family finally arrived in the United States in 1991, Domingo, then 15, found himself struggling to adapt to a new environment. Fortunately for him, his teachers quickly saw his potential.

“I turned in work to my ninth grade math teacher, Mr. Klass, during my first semester, and he told me to do it again,” said Domingo. “He said he knew I could do better. I was very blessed with teachers who looked out for me.”

After graduating high school, Domingo attended Mount San Antonio Community College and then transferred to California State University, Long Beach. He intended to become a physical therapist and complete the university’s bachelor’s degree in the subject, but the program closed the semester he arrived.

“I thought I would just try to wrap up a major as quickly as possible,” he explained. “The first major I saw that I could finish in three semesters was psychology. I figured I’d do that and then immediately apply to the master's degree physical therapy program.”

An encounter in his first university-level psychology class altered his outlook.

“My whole life changed because of one person,” stated Domingo. “I took a research methods class in psychology and the professor, Dr. Robert Kapche, invited me to his office one day. He told me that he thought I was smart and recommended me for a research internship. It was highly competitive, but he saw something in me.”

The undergraduate internship was with the psychology department at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. The group was researching the cognitive-linguistic properties of the Tagalog language, the native language of the Philippines. Domingo spent eight weeks during the summer of 1998 working in the university.

“It was exciting,” remembered Domingo. “My original intention was to go into physical therapy and serve people, but eventually my interests shifted over to the realm of human cognition and getting to understand how people think and process information. I realized that studying and working in the psychology field was a different way to help people.”

Domingo applied for graduate school in the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities a year later. “The person I worked under initially in 1998 became my graduate advisor all through my six years of graduate school,” he said. “All these doors opened for me. I never fathomed myself being an academic, let alone being in psychology. It felt like destiny to me.”

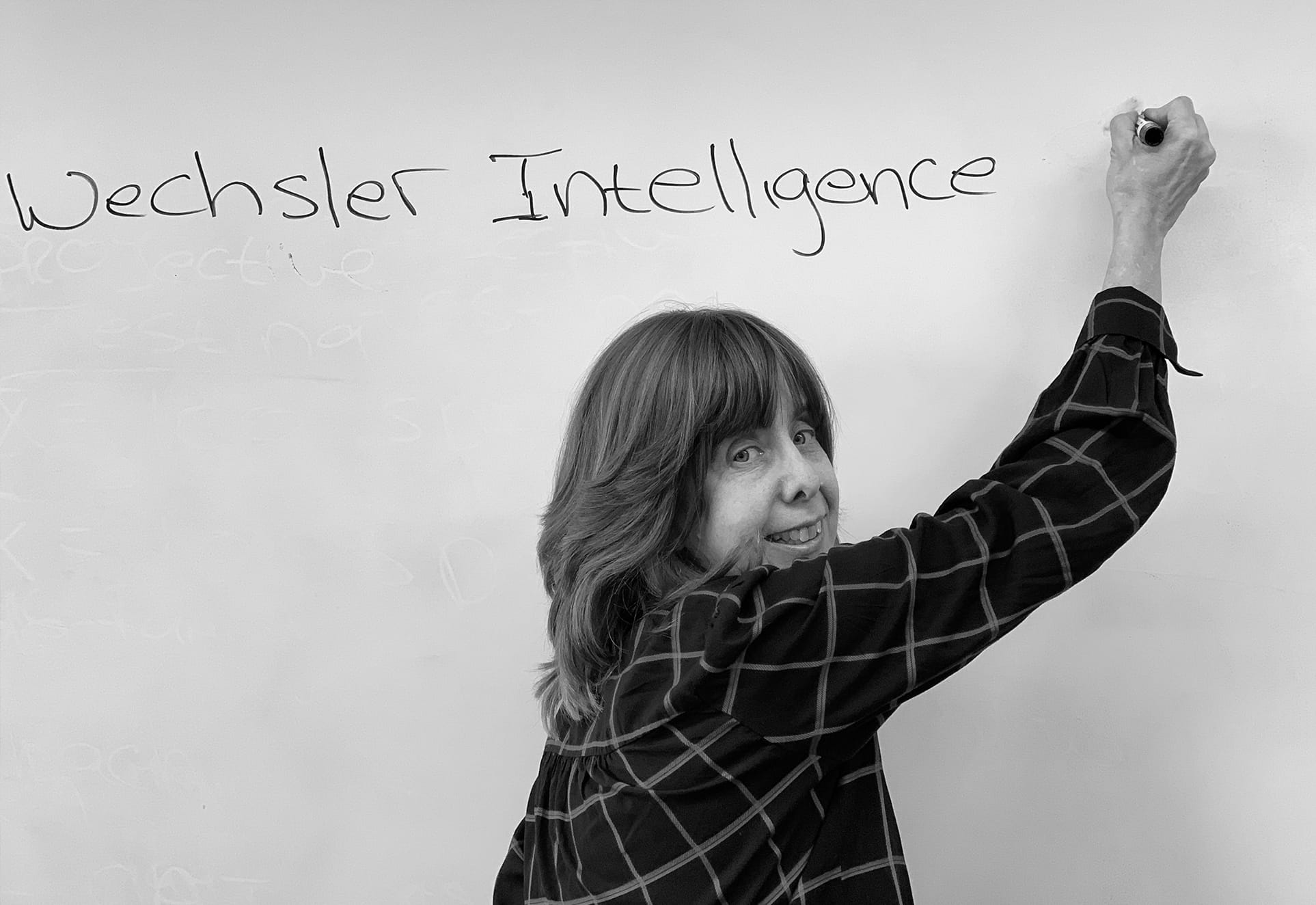

In 2005, he earned his Ph.D. in cognitive and biological psychology. His dissertation focused on the language processing involved in the native speakers of Tagalog. During graduate school, he held an assistantship teaching psychology in the undergraduate school.

“I always taught the same course, so I was able to refine it,” said Domingo. “I think that’s where I knew I wanted to shift towards teaching instead of researching. There’s something in that moment when you realize a lightbulb is switching on in a student’s head. While I valued research and the ability to bring something new to the table, I felt myself drawn to teaching. Teaching is challenging in of itself: you need to be so familiar with the material that you can translate high level concepts into digestible bits.”

After finishing graduate school, Domingo taught a range of classes in both college institutions and high schools. He said that the mix—undergraduate students, graduate students and high school students—was a challenging but rewarding experience.

“You have to have a very good mastery of the material,” he said. “You need to understand the broad scope of the profession but have that skill to break it down into simple terms.”

“I never envisioned this is where I would be—this is a part of my journey in becoming a citizen of the United States. This country adopted me and gave me a life that I couldn’t have had elsewhere.”

Aldwin Domingo

In 2015, Domingo was offered the opportunity to manage the Touro University Worldwide online BA and MA programs in psychology. His responsibilities included teaching, program review and managing faculty members. “I looked at how and why programs were put together and what sequences there were,” explained Domingo.

While teaching online was new for Domingo, he said he eventually found it liberating. “It’s a different way to interact with students,” he explained. “All I see is their names and I respond to students in terms of what they post. It levels the playing field; everyone has the same say in what they can contribute. Additionally, since our program is online, I find that the majority of our students are either older or working professionals and they can contribute a lot more personal experiences than in a traditional classroom.”

A year later, he was officially named school director. The school has more than 300 students and over 20 faculty members. He believes the position is the best of both worlds: he’s able to guide students as well as help faculty members with their courses. “It’s the best job I ever had,” admitted Domingo. “I am able to grow, both by helping students and my fellow faculty members.”

“I’m very proud of the students who have finished the program and asked me for recommendations to apply for the Psy.D. here or in another program or even another field,” he added.

Graduation is especially meaningful for Domingo. Some students fly in for the ceremony. “I finally am able to put a face to the name of a student who I worked with for so long,” said Domingo. “When they walk across the stage to receive their degree, it doesn’t get more personal than that.”

Despite his many accomplishments, Domingo said he never lost sight of the journey his family made.

“I don’t think my parents could have fathomed that I would earn a doctorate and be where I am,” he elaborated. “I never envisioned this is where I would be—this is a part of my journey in becoming a citizen of the United States. This country adopted me and gave me a life that I couldn’t have had elsewhere.”

Favorite Quote

“Immigrants get it done.”

Graphic Novelist

Domingo draws and writes in his spare time and has published two graphic novels. His favorite comic book writers are Brian K. Vaughan and Alan Moore.

Interesting Fact

Domingo is a fan of the Japanese studio responsible for the critically acclaimed films, Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke, and My Neighbor Totoro. He has instilled that love in his daughter as well. “She knows Totoro as much as Mickey Mouse,” he laughed.